Scratching the surface: the skin microbiome and atopic dermatitis

The epidermis: more than meets the eye?

Atopic dermatitis (AD), or eczema, is a well-known skin condition affecting millions of adults and children worldwide.1 What is less well known and understood is the role of the skin microbiome in the pathophysiology of AD.

The Skincare & Dermatology 2019 special report, recently issued in The Times, reflects on whether skin can ever be too clean, and how an imbalance of the skin microbiota (i.e. dysbiosis) as a result of modern living could be exacerbating inflammatory skin conditions such as AD.

In this commentary, we discuss the association between AD and the skin microbiome, and consider how healthcare professionals can help patients with AD to correct alterations in their skin microbiota and improve their symptoms.

Atopic dermatitis and the skin microbiome

The incidence of allergic reactions and inflammatory conditions such as AD and psoriasis has increased over the last several decades, and attention is now shifting towards the idea of a healthy bacterial balance and how it can not only protect the skin, but also help repair it.

The epidermal microbiome, in essence, is the community of organisms that live on the skin, including bacteria, viruses and fungi. It represents a finely tuned ecosystem that regulates more aspects of our health than we appreciate, much like our gut bacteria. Therefore, dysbiosis of this ecosystem can have far-reaching consequences.

“Your skin microbiome is already under pressure, as the skin is quite acidic. For example, sebum, the spot-causing oil, is actually antibacterial. So the microbiome already has a bit of adjusting to do to that. It’s a very intricate balance on the skin and when the regulation fails, you get problems. For example, eczema is linked to the overgrowth of a certain bacteria.”

Professor Carsten Flohr

Consultant dermatologist and eczema specialist

Guy’s & St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust

Our skin microbiota plays a role in skin homeostasis and inhibiting overgrowth of potentially harmful pathogens.2 The skin microbiome of patients with AD differs substantially from that of healthy skin, however, with a high prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus colonisation and secondary infections. It is still unclear whether changes in the skin microbiota contribute to AD development or occur as result of the damaged skin barrier and immune system dysregulation.3

S. aureus is commonly found on human skin and mucosa, with around 20% of the healthy population persistently carrying S. aureus on their skin. In patients with AD, prevalence can vary between 30% to 100% depending on the patient age and disease severity.4,5 The prevalence of S. aureus on the skin can also vary within the same patient, with an average prevalence of 70% on lesional skin and 39% on non-lesional skin.5

In lesional and non-lesional skin, disease severity increases with higher S. aureus colonisation densities.4,5 The microbiota composition across diverse body sites is affected, with a decrease in microbial biodiversity and a predominance of Staphylococcus species (particularly S. aureus) during an AD flare.6,7

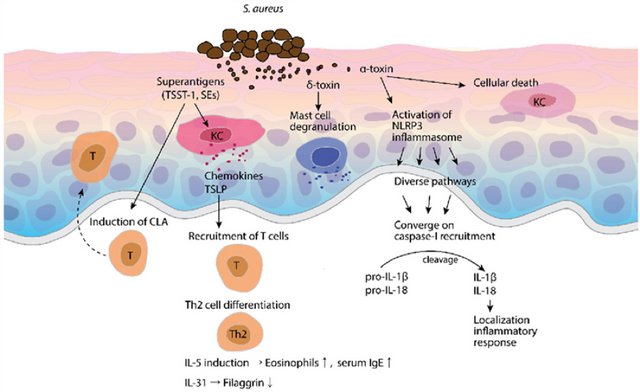

Pathogenesis or symptom exacerbation by S. aureus is due to expression of multiple virulence factors, as illustrated in the figure below.8 Other microorganisms that are normally found on healthy skin, such as fungi in the Malassezia genus, may have a role in promoting skin inflammation in patients with AD.9

Reversing skin dysbiosis in clinical practice

In patients with AD, the use of antimicrobial or anti-inflammatory treatments can alter the microbial diversity and proportions of Staphylococcus. In the absence of recent treatment, AD flares are characterised by low microbial diversity. However, a reduction in the prevalence of S. aureus and improved bacterial diversity is observed during AD flares following recent or intermittent AD treatment, and the dysbiosis is reversed during treatment and recovery.6

“Eczema is not just an unpleasant and painful condition, but it also represents a breakdown in the skin barrier. This can then leave the skin more open to infection or other kinds of irritation and people who have very severe eczema are more likely to have hay fever as well, for example.”

Professor Carsten Flohr

Consultant dermatologist and eczema specialist

Guy’s & St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust

In order to induce the resolving flare stage and make a post-flare recovery, where the full microbial diversity is restored with low population levels of Staphylococcus, patients should use their AD treatment consistently and continuously over a period of time.10

Physicians and other members of the care team therefore have a responsibility to actively support patients in adopting and maintaining a suitable treatment regimen in order to effectively manage their AD and maintain a healthy skin microbiome.

To learn more about the pathophysiology of S. aureus infection in AD, visit our online course ‘Immune system and pathophysiology of AD’. To find out more about current treatment guidelines and how different treatments work in AD, explore our other online courses:

About Action Eczema

Action Eczema is a global learning community designed to support all health professionals involved in the care of patients with AD. We provide a range of online CME courses to facilitate increased knowledge, competence, confidence, and performance related to eczema care.

Action Eczema recently appeared in the Skincare & Dermatology special report, which explores the psychological impact of AD and highlights the responsibilities of physicians in psychodermatological patient care.

We proudly support the Primary Care Dermatology Society’s call for better education and workforce training in dermatology.

References

- Karimkhani C, Dellavalle RP, Coffeng LE, et al. Global skin disease morbidity and mortality: an update from the Global Burden of Disease study 2013. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(5):406-412.

- Rademacher F, Simanski M, Glaser R, Harder J. Skin microbiota and human 3D skin models. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27(5):489-494.

- Byrd AL, Belkaid Y, Segre JA. The human skin microbiome. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16:143.

- Tauber M, Balica S, Hsu CY, et al. Staphylococcus aureus density on lesional and nonlesional skin is strongly associated with disease severity in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(4):1272-1274.e1273.

- Totte JE, van der Feltz WT, Hennekam M, van Belkum A, van Zuuren EJ, Pasmans SG. Prevalence and odds of Staphylococcus aureus carriage in atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(4):687-695.

- Kong HH, Oh J, Deming C, et al. Temporal shifts in the skin microbiome associated with disease flares and treatment in children with atopic dermatitis. Genome Res. 2012;22(5):850-859.

- Baurecht H, Ruhlemann MC, Rodriguez E, et al. Epidermal lipid composition, barrier integrity, and eczematous inflammation are associated with skin microbiome configuration. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(5):1668-1676.e1616.

- Park K-D, Pak S, Park K-K. The pathogenetic effect of natural and bacterial toxins on atopic dermatitis. 2016;9(1):3.

- Glatz M, Bosshard PP, Hoetzenecker W, Schmid-Grendelmeier P. The role of Malassezia spp. in atopic dermatitis. J Clin Med. 2015;4(6):1217-1228.

- Baviera G, Leoni MC, Capra L, Cipriani F, Longo G, Maiello N, et al. Microbiota in healthy skin and in atopic eczema. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2014.