Atopic dermatitis: moving beyond the prescription pad

More than skin deep

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is one of the most common skin conditions, affecting more than 230 million people globally.1 AD can vary in severity, but typically involves itchy, dry, cracked and red skin. As people suffering with eczema will know, the condition also profoundly affects quality of life.

While the correlation between poor body image and low self-esteem is well-established, researchers have only recently described the increased levels of depression and anxiety experienced by patients with AD. The Skincare & Dermatology 2019 special report, issued in The Times this month, explores the topic of mental health, and reports that psychological issues arising from skin conditions are fuelling the growth and importance of psychodermatology.

In this commentary, we also shift the focus away from the physical manifestations of AD, and direct the conversation towards the consequential feeling of being ‘unhappy in our skin’. We reflect on the mental health burden associated with AD, and discuss how healthcare professionals can incorporate the tools of psychodermatology into patient care.

The mental health burden of atopic dermatitis

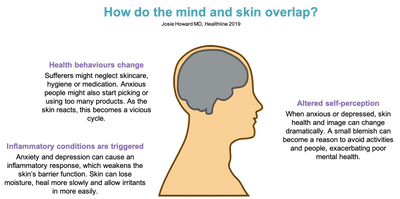

Anxiety, depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) are inextricably linked to chronic skin conditions, either as a by-product of a skin issue or even as the catalyst for one. Our image-obsessed culture, which holds youthful, flawless skin as the ideal, can generate considerable pressure and worry for people with AD.

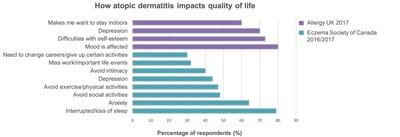

AD can affect patient quality of life in a myriad of ways. For example, in a Canadian survey on the impact of AD over the previous 2 years, 48% of the respondents avoided social activities, 40% avoided intimacy and 30% had to give up certain activities entirely or change careers.

Dr Anjali Mahto, consultant dermatologist at the Cadogan Clinic, finds that skin diseases negatively impact mental health in most of her patients. Dr Mahto says: “If you have a chronic skin condition like acne or rosacea that has no ‘cure’ so to speak, that can be really hard to deal with psychologically. It’s unpredictable and you can end up planning your life around your ‘good skin days’.” She continues, “I would say the majority of my patients have an underlying mental health concern. It’s hard not to when you’re battling a chronic skin condition that has a tendency to flare up at the worst possible times. A lot of the problems can centre around feelings of control or lack thereof.”

Other physicians have also found that undesirable behaviours can develop as a result of their patient’s disorder. “Some of the most pressing psychological issues that go along with skin conditions are anxiety and depression, though some OCD-type conditions can manifest via the skin,” says Dr Paul Charlson, president of the British College of Aesthetic Medicine. “For example, dermatillomania, or compulsive picking of the skin.”

Dermatology: going beyond the superficial

Psychodermatology has long been included on the medical curriculum, but it’s finally starting to emerge as a field in its own right as a response to a growing mental health crisis.

Dr Charlson says: “There are a few dedicated psychodermatology units up and down the country, but on the whole it’s something everyone needs to be mindful of. When I do a consultation with a new patient, body dysmorphia is part of the test. You look for those verbal and non-verbal clues. Part of the therapeutic relationship is supporting a patient and making sure they don’t lose faith.”

However, access to care remains an issue. Dr Angelika Razzaque at the Primary Care Dermatology Society (PCDS) explains: “Waiting times to see a GP vary from same day for acute or emergency issues to weeks for routine appointments, so increasingly online advice is being sought, or just asking family or peers.”

“Patients often have a bad experience as GPs are not trained in dermatology, which is a paradox given that 25% of consultations are skin related. Patients often perceive their skin condition possibly as minor compared to more serious problems, such as diabetes or heart disease, and yet most people with skin conditions have worse mental health than people with diabetes.”

Dr Angelika Razzaque

Primary Care Dermatology Society

Both Dr Charlson and Dr Mahto agree that it is their responsibility to look for warning signs of suffering in a patient and refer them to a specialist where necessary. Dr Mahto offers “almost all” her patients psychiatric or psychological referrals to ensure their needs are being met. “I ask them, ‘Do you feel ashamed of your skin? Is it a big deal for you to be here without make-up on?’ Those kinds of questions can provide a valuable window into someone’s mental state,” she says.

The duty of care for a patient with AD goes beyond just the superficial, and as a consequence of our increasingly aesthetic culture, practitioners will need to take a holistic view to ensure they support the mental as well as physical wellbeing of their patients.

Visit our online course ‘Disease burden and quality of life in atopic dermatitis’ to learn more about the psychological impact of AD in adults and practical care considerations.

About Action Eczema

Action Eczema is a global learning community designed to support all health professionals involved in the care of patients with AD. We provide a range of online CME courses to facilitate increased knowledge, competence, confidence, and performance related to eczema care.

Action Eczema recently appeared in the Skincare & Dermatology special report, which explores the psychological impact of AD and highlights the responsibilities of physicians in psychodermatological patient care.

We proudly support the PCDS call for better education and workforce training in dermatology.

References

1. Karimkhani C, Dellavalle RP, Coffeng LE, et al. Global skin disease morbidity and mortality: an update from the Global Burden of Disease study 2013. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(5):406-412.